Veritas: Part I

Conversion of a Prodigy

Credit: San Francisco Chronicle/Hearst Newspapers via Getty Images

The testimony of a two-time gold medalist at the International Mathematical Olympiad who found his way to the Catholic Church.

By Chris and the Editorial Staff

Alexandr Wang, CEO of ScaleAI who was crowned the world's youngest self-made billionaire, declared in a 2021 blog post:

Science is active thinking. Religion is lazy thinking. There is a reason why most human progress and quality of life improvement is derived through the scientific method.

Modern culture has repeatedly attempted to pit science against religion, casting the latter as superstition that should be shunned by the educated. But is it true that humanity, especially the most intelligent members of our society, has advanced beyond the need for religion? Is religious belief simply the filler in the void of our human understanding? Is atheism indeed the most rational mindset?

Let’s hear from Evan O’Dorney, a mathematician who shared his story with me in autumn 2024.

Evan O’Dorney (b. 1993)

Three-time Putnam Fellow, two-time International Mathematical Olympiad gold medalist, Harvard A.B. and Princeton PhD in math.

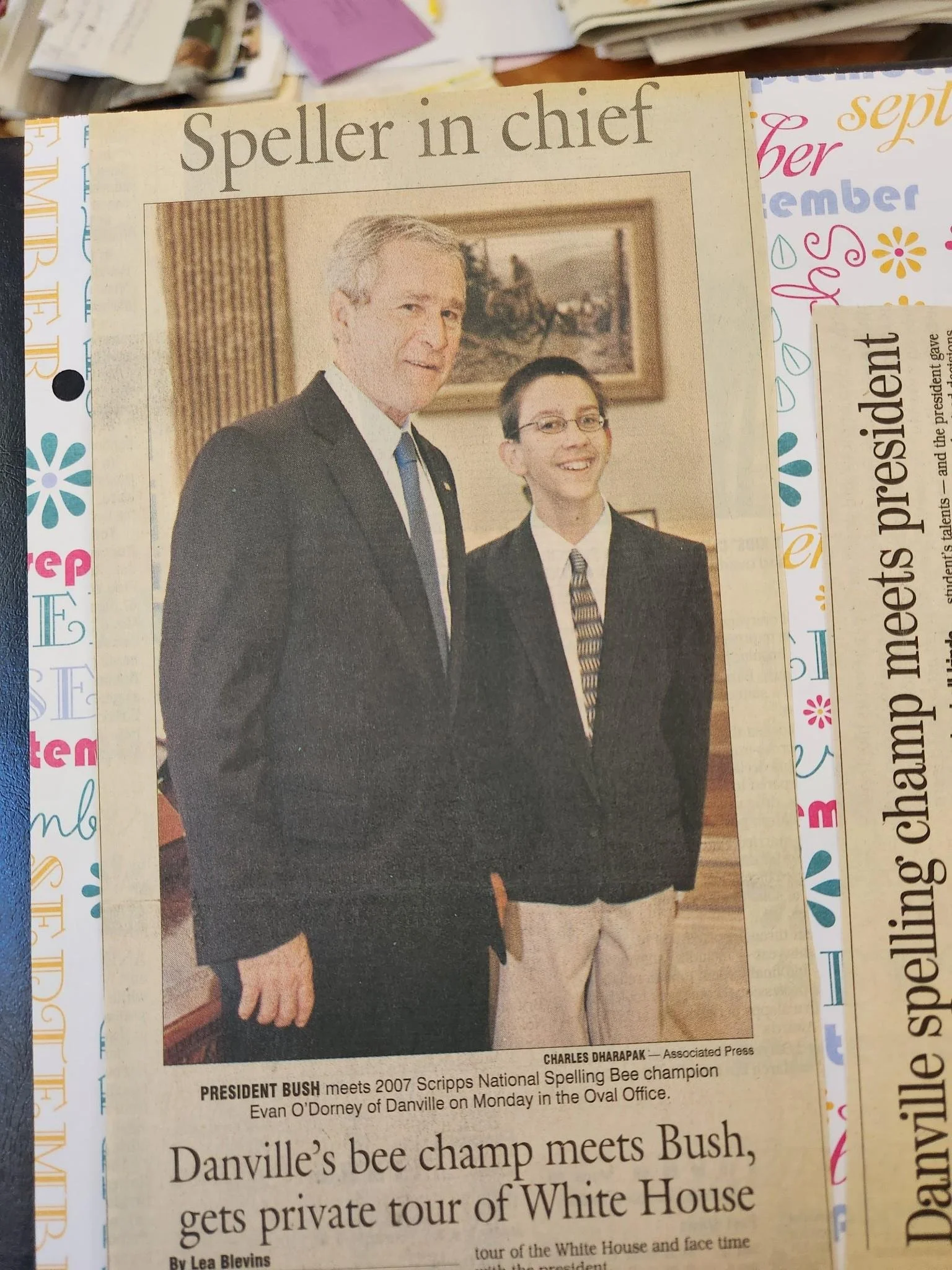

In early September of 2024, I emailed O’Dorney to introduce myself and request a call to learn more about his life story after learning that he’s Catholic. In his reply, he kindly agreed to the call and also pointed out that I had misspelled “Alcibiades” in one of my articles. This was wholly unsurprising, as I was aware that he had won the 2007 Scripps National Spelling Bee.

But the spelling bee is arguably the least impressive of his accomplishments. His accolades include a three-time Putnam Fellowship, the 2011 Intel Science Talent Search (which came with a $100,000 prize), and two gold and two silver medals at the International Mathematical Olympiad. O’Dorney also won a slew of other contests and honors, including the 2015 Churchill Scholarship while he was a senior at Harvard, where he graduated summa cum laude.

During his doctorate program at Princeton, he studied under Fields Medalist Manjul Bhargava, who gave him a “stunningly beautiful” math problem that O’Dorney contentedly mulled over for more than five years, culminating in a dissertation titled “Reflection theorems for number rings.” Currently a math postdoc at Carnegie Mellon, he specializes in number theory.

One month after that email, I spent an hour with O’Dorney on Google Meet, where he opened up on a topic that went largely undiscussed in his previous interviews: his conversion to Catholicism.

At age 17, Evan O’Dorney solved a number theory problem that stumped Stanford professors, and as a result won the 2011 Intel Science Talent Search along with its $100,000 grand prize.

Grand Simple Day

O’Dorney described growing up in Danville (a 45-minute drive from San Francisco) in a Christian family that often church-shopped across many Protestant churches. O’Dorney developed a keen interest in music, picking up classical composition, singing, and piano. At age eight, he was invited to a boys’ choir at a Catholic cathedral, sparking his mother’s interest in the Catholic faith. His mother eventually led the family to join the Catholic Church, and O'Dorney was baptized at age nine. Initially, the Catholic Church felt like just another church to him, but then he had a change of heart as a teen:

I was 15 and had questions as teenagers do. We came to hear that there was a homeschooling family that was having a series of video showings in their house on Theology of the Body as presented by Jason Evert. When I went, I was struck. I mean, the video—it’s maybe a little bit more light or even a little cheesy than what I’m used to, but I could see that there was a lot of deep wisdom in there, talking about how we’re created for love, made male and female—all God’s plan.

Evert’s Theology of the Body series is based on St. Pope John Paul II’s 129 lectures of the same name given between 1979 and 1984. These lectures explained the Catholic Church’s teachings on the dignity of the human person, the sacredness of marital love, and the idea that the marital life and the sexual act are rooted in selfless, life-giving love. In a world where hedonism is increasingly prevalent, O’Dorney discovered truth in these countercultural teachings.

O’Dorney went on to tell me:

I saw–and there were coincidences surrounding the day of that first video that I take to be signs of God–that this was the change of heart He wanted for me. I look back on that day every year; I call it “Grand Simple Day,” February 7, 2009, and celebrate it. I see that the Catholic Church has real answers, the foundations being 2,000 years old and very consistent in preaching the many messages and doctrines we have.

Inspired by these revelations, O’Dorney went on to become a devout Catholic. As mentioned in his interviews with Texas Math Mundo and Christian Union, he joined the Rosary group at Harvard, and to this day his daily routine includes reading the Bible alongside a devotional book and praying the Rosary, despite his busy and unpredictable schedule: “I know that there are plenty of other Christians around the world [who] are subject to time pressure, so I can pray in union with them.”

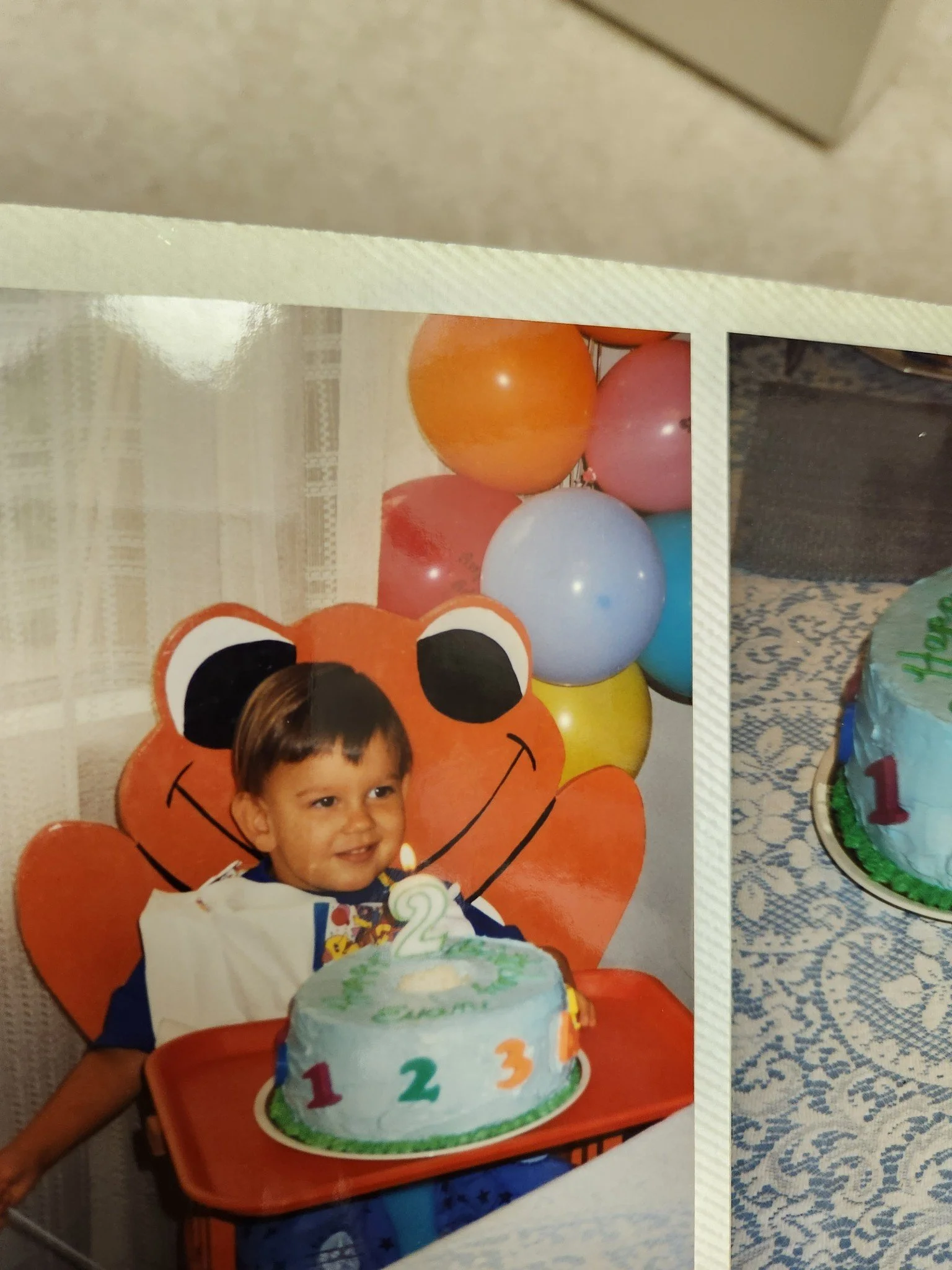

O’Dorney mastered multiplication by the time he was a toddler.

Miracles

O’Dorney and I discovered we share a common view about an aspect of our faith: the preponderance of well-documented miracles of the Catholic Church sets it apart from all other religions.

Part of the reason I agreed to this interview is that you put together Marian apparitions, Eucharistic miracles, and demonic possession, which in theology would be minor details in three separate classes. I really sympathize with that—putting those three things together—because they’re all evidence that science isn’t enough. In our age, science has advanced tremendously, but there’s a lot of scientism [the belief that science is the only legitimate path to knowledge], and yet there’s always this fascination with the supernatural or the paranormal as well.

I have to say the miracles did play a major role [in my faith]. For instance, when I first heard about Medjugorje, even though it hasn’t been fully approved by the Church—it’s a step-by-step process—it was like, wow, there’s a large-scale report of miracles taking place in our own time. It’s happening in the Catholic faith, and no other religion has anything comparable to this. So I got interested in that.

O'Dorney is referring to Medjugorje, a small town in Bosnia and Herzegovina, where Marian apparitions have been reported since the 1980s. The Church has indeed not yet approved the authenticity of the apparitions, but in September 2024, it approved devotions linked to Medjugorje thanks to the unusually high volume of spiritual conversions that have taken place among visitors to the site.

But I challenged him: What about the common argument that miracles are improbable, and that natural explanations are more probable than the occurrence of miracles? He responded:

It all depends on your starting point, doesn’t it? If you start out by just observing the laws of physics and knowing that they imply that it’s astronomically improbable for a dead body to recover its living state, then your conclusion will be that the resurrection was faked somehow. But if you step out of the physical and the mathematical, and if your heart is open to reading in history a story of God’s search for man—a story arc spanning many millennia—then you see that we could never have written it any better than He did.

Here O’Dorney is citing a thought often attributed to C.S. Lewis: “Every other religion is the story of man’s search for God; but Christianity is the story of God’s search for man.”

I speak of stepping out of mathematics because this is also how I was able to appreciate music better. Some say that Bach’s music is the most mathematical, and it’s true there are some numerological designs in some compositions. When he writes triple fugues, taking three themes and permuting them in all six ways, there’s a mathematical design, but that doesn’t explain all the notes he wrote, especially in some pieces. Stepping back, you realize there’s emotion to it—movements of the heart. “Emotion” is an approximate word here, as we use it to describe states like happiness and sadness that are more lasting, but even a rise or fall in a melody says something that speaks to the heart.

I then mentioned to him that a childhood friend of mine had insisted miracles are not worth believing without a double- or triple-blind study, and asked for his thoughts on the matter. O’Dorney explained:

If you try to set up something like a double-blind study of miracles, you're trying to say that they consistently happen. By definition, they don’t; they’re gifts from God to particular people, and you can’t anonymize [them]. … Many people go to Lourdes to get healed; they say they were crippled, then throw away their crutches, and you can find many discarded crutches… If your heart is open, you see this as a lot of evidence. And ditto, when people study things like the Shroud of Turin and the tilma of Guadalupe, they find strange things; [for example] the tilma has colors but tested negative for known dyes. In that sense, you’re using the methods of science to come to a conclusion: there’s no physical explanation under what’s currently known for what happened, and that’s about as far as science can get, because science by its nature has to be open to new discoveries.

Philosophy

When I asked O’Dorney to share what role philosophy played in forming his faith, he responded:

As far as philosophy goes, I've never been into philosophy a lot; neither has my family. If my mom and I tried to read a philosophy book, we’d be looking at each other and shaking our heads. We’re just not versed in that language, and I’m picking it up bit by bit. On the other hand, the fact that works like the Summa Theologiae [a 13th century work by St. Thomas Aquinas] exist and that someone could go through, ask a bunch of questions, and lay out the answers in logical order gives me a lot of faith too. Not all religions are philosophically equally coherent. For instance, the story of Scott Hahn, who tried to write something like the Summa for Protestantism and was led to a crisis, is a powerful witness.

Scott Hahn is a former Presbyterian pastor who experienced a change of heart similar to O’Dorney’s. Hahn converted to Catholicism after his theological research convinced him that the Catholic stance on sexual morality was the most consistent with divine law, and he went on to become a prominent Catholic theologian. His wife Kimberly Hahn, despite her initial struggles with Catholic doctrines, eventually came to the same conclusions and became a Catholic apologist and author.

O’Dorney continued:

In math, there’s something analogous. Something like the proof of Fermat’s Last Theorem or the classification of finite simple groups are huge projects that have been carried out, and research builds on itself from century to century, from decade to decade, and people solve problems. That pattern is what you expect in a field based on something real, where the results are true. Obviously, there are mistakes in math—people write up proofs, even get them into print, and it turns out there are errors—but the errors do get corrected. It’s not a field with a constant rechallenging of basic assumptions, [unlike] philosophy or even economics.

The former “speller in chief” has spotted two typos so far on this website.

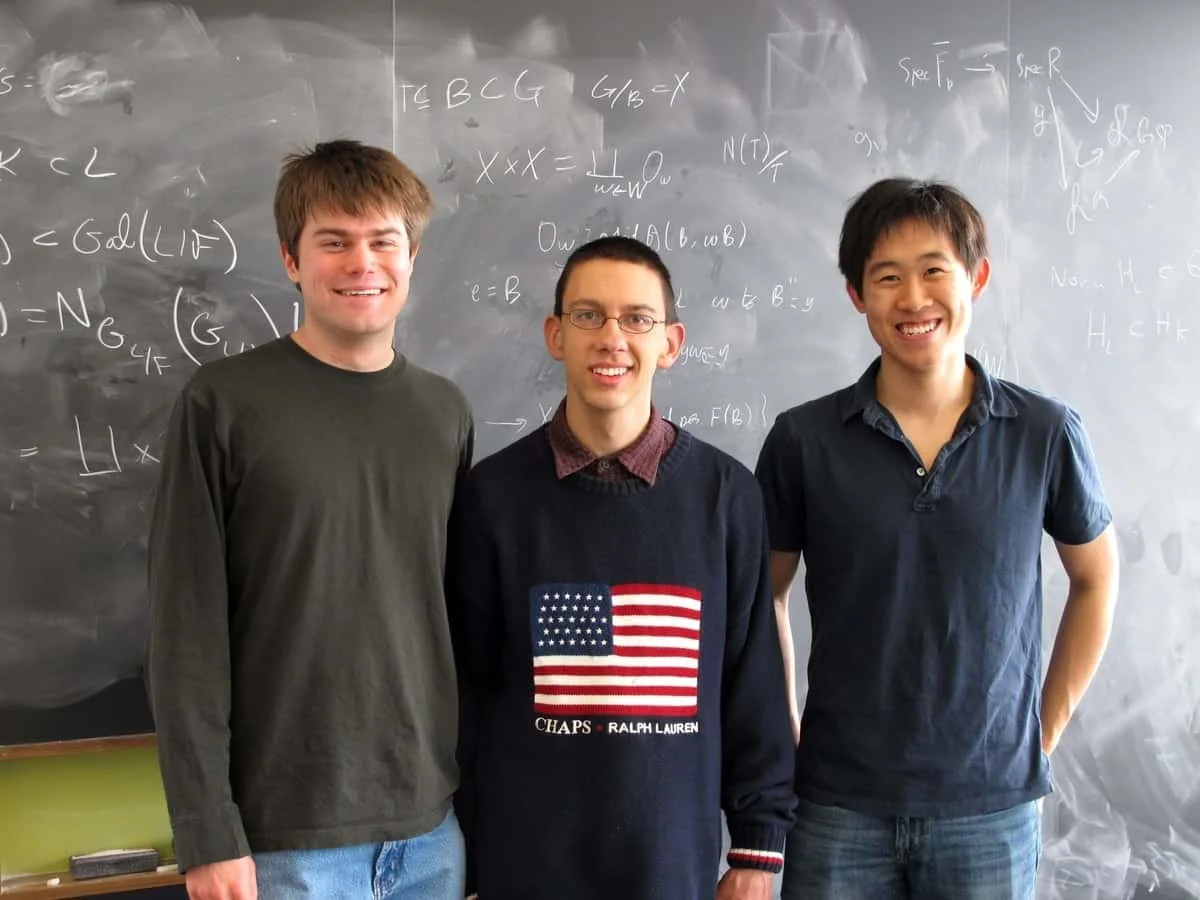

Evan O’Dorney with his 2012 Harvard Putnam teammates Eric Larson and Allen Yuan. The Putnam is the world’s most prestigious math competition for college students. O’Dorney was a three-time Putnam Fellow, placing in the top five each time.

The One True Church

Having spoken to him firsthand, I agree with the San Francisco Chronicle that O’Dorney has a “patient, thoughtful drawl” like Mr. Rogers, also exuding a similar humility and kindness. But during our interview, he also did not shy away from expressing unpopular views such as his endorsement of the Catholic Church’s strong stance against abortion.

Right now we’re fighting a culture war on things like abortion, where it seems like the Christian church is the only organization willing to take a stand…. So religion really, and especially the Catholic Church, because we’ve got 2,000 years of solid thought, we’re able to feel our way through the maze of current events with an advantage.

O’Dorney predicts that within a few hundred years, humanity will look back on abortion as a large-scale human tragedy. If this characterization sounds like hyperbole, consider the fact that over 1.7 billion abortions have taken place worldwide since 1980, representing over 20% of the current human population.

O'Dorney concluded the interview with the following message to non-believers:

I would say that if you look at the religions of the world, you see that a lot of them are similar in some ways. The Greeks used to have this pantheon of gods they worshiped; the Hindus still have that kind of thing, this worship of idols. You find it in Polynesia and so forth.

But then there are some religions that are more different from the others. The idea that God spoke to His people and that there’s a particular book that’s the word of God seems unique to Judaism and the religions that have flowed out from that. Then you ask, of those, which one seems to be proceeding and not somehow caught up in the past or in a rigid way of seeing things, which one seems to be alive, and which one also seems to have done a lot of good for the world. You look at the history of the university.

As a number theorist, I like to cite one random example: the first exponential Diophantine equation was written down and solved by Fra Luca Pacioli, a Franciscan friar in the 1400s. [Look at] the courage to ask new questions and think about what it is about the worldviews of these religions that encourages people or discourages people from doing science and doing all the things that are of benefit to mankind.

Life Beyond Math

I entered the interview eager to learn how a highly intelligent mathematician became Catholic. What I did not expect to discover, however, was that he’s not merely a believer but one who is obviously deeply in love with the faith, eager to evangelize in small but meaningful ways.

At one point in our conversation, he asked me where I live and what I do for a living, and in return I asked how he likes his postdoc job at Carnegie Mellon, expecting him to discuss his day-to-day life as a mathematician. Instead, he gleefully recounted this story:

I’m liking it. I'm a postdoc. This is my second postdoc. The first one was at Notre Dame. I did enjoy being at a Catholic school, being able to share my faith in a deep way. There was even one student who became Catholic upon taking my class. He was from China, didn’t grow up with any faith, and he knew I was Catholic. I dropped some hints at the beginning of the semester and sometimes talked about Saints’ days. He kept coming up to me after class and asking questions about my faith, and he could tell I was genuine. That spring, or maybe a year later, he announced that he was enrolling in RCIA [Rite of Christian Initiation of Adults], and his sponsor was another person in that same class of mine.

At the very end of our conversation when I was about to thank him and say good-bye, O’Dorney mentioned he’s an associate at Opus Dei, a Catholic organization founded by St. Josemaría Escrivá, that engages in charity, social work, and spirituality training among mostly lay Catholics. He commits himself to attending daily Mass, praying the Rosary daily, and receiving spiritual direction. Without skipping a beat, he volunteered to introduce me to the organization by connecting me with their members in NYC.

Of course I said yes.

Evan O’Dorney: an academic mathematician and practicing Catholic